Still swatting flies in Colombia

Posted by Adam Isacson

Iraq has made plain that the United States is really, really bad at dealing with insurgencies. Helping elected governments assert control over territories dominated by people who murder civilians sounds like a noble goal. But our fundamental misunderstanding of "counterinsurgency" - viewing it as a mainly military effort, neglecting poverty and civilian governance, treating the locals with suspicion or even abusing them - keeps making the situation worse.

In what is currently the nation's number-two best-selling non-fiction book, Washington Post reporter Thomas Ricks takes the U.S. defense establishment to task for "unprofessional ignorance of the basic tenets of counterinsurgency warfare." Warned expert Andrew Krepinevich in a year-old Foreign Affairs article, "Having left the business of waging counterinsurgency warfare over 30 years ago, the U.S. military is running the risk of failing to do what is needed most (win Iraqis' hearts and minds) in favor of what it has traditionally done best (seek out the enemy and destroy him)."

This is a big, fundamental problem, because the "war on terror," as currently fought, keeps leading us into difficult counterinsurgency missions. Right now, the Bush administration is facing insurgents directly in Iraq and Afghanistan, and it's not going well. Israel, the United States' closest ally in the Middle East, just confronted a locally popular irregular army (Hezbollah doesn't really fit the definition of an insurgency) with a strategy based on aerial bombing, with hugely frustrating results. Meanwhile, Washington is supporting other governments' counterinsurgency campaigns in Colombia, the Philippines and Nepal.

I work a lot on Colombia, which is by far the biggest U.S. military aid recipient outside the Middle East - $3.8 billion in military and police aid since 2000, making up 80 percent of our entire aid package to Colombia during that period. This aid, under a framework called "Plan Colombia," started out as an effort to reduce the flow of illegal drugs from Colombia. In the wake of September 11, though, the Bush administration got permission from Congress to allow the aid to be used to fight Colombia's insurgency, principally two Marxist guerrilla groups founded in the mid-1960s.

On a visit in late July, I participated in a panel discussion in Colombia's Congress, hosted by Luis Fernando Almario, a congressman from the department (province) of Caquetá in southern Colombia. Caquetá is about the size of South Carolina, but with only about 450,000 people. Many of them are migrants who came from elsewhere in Colombia within the past generation, cut down some jungle and have since tried to scratch out a living as farmers. Most of the population (58 percent, according to the Colombian goverment [Excel file]) lives below the poverty line.

The department has been all but abandoned by Colombia's government. As a result, the FARC guerrillas (who often issue threats to Congressman Almario) have easily dominated it for decades, while right-wing paramilitaries have more recently established themselves in larger towns. Caquetá has also been a center of the trade in coca, the plant used to make cocaine; in 2005, it ranked seventh among Colombia's 32 departments in the number of acres planted with coca.

In the past few years, Caquetá has been one of the main battlegrounds in the Colombian government's U.S.-supported counterinsurgency campaign. Since 2004, it has been at the center of "Plan Patriota," a large-scale military offensive that aims to re-take territory from the FARC. About 18,000 Colombian Army troops have swept through Caquetá and neighboring departments, supported by dozens - at times hundreds - of U.S. military personnel and contractors doing logistics, intelligence, and who knows what else. Behind the troops have come spray planes flown by U.S. contractors, fumigating tens of thousands of acres of coca fields with herbicides.

Congressman Almario does not oppose "Plan Patriota" per se - at least, he doesn't oppose the idea of the Colombian government seeking to assert control over its own territory. But he wonders what will happen when the troops and police leave Caquetá to fight elsewhere, as they may actually be doing already. He wonders when the residents of Caquetá's rural zones will begin to see infrastructure projects, a judicial presence, land titling, health, education and other evidence that Colombia's state is really there to stay.

|

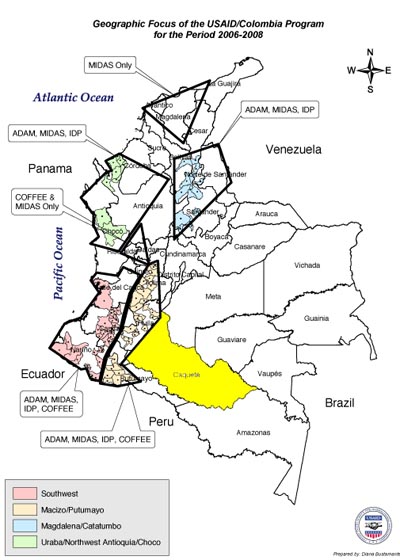

| Caquetá, in yellow, is left off of USAID's map of priority regions. Map from the U.S. embassy in Colombia (PDF file) |

The answer, tragically, appears to be "not anytime soon." Very little non-military aid has made its way to Caquetá: a total of about $5.8 million in development assistance since 2000, according to the UN Office of Drugs and Crime. [See page 48 of this long PDF file.]

But it gets worse. Late last year, Congressman Almario learned that the U.S. Agency for International Development's future plans for aid to Colombia don't include Caquetá at all. To his surprise, his province is completely cut off from USAID's plans to spend over $300 million on alternative-development projects in Colombia during the next five years.

Almario asked the "Social Action" section of the Colombian presidency's office how this could be. He received from them a letter [PDF in Spanish] "transmitting the response given by USAID-Colombia." The congressman shared it with me, and it is a remarkable document. It is hard to find such an eloquent demonstration of how badly the U.S. government continues to misunderstand its mission. Here is what it said (emphasis is mine).

Why was Caquetá not chosen as a focus area for our programs? Even though the department registers a presence of coca cultivations (approximately 7,000 hectares in 2004), it lacks sufficient economic potential and there is very little private-sector investment. In addition, although national and local will exists to support licit economic activities, the department registers very high levels of conflict and FARC presence. This circumstance makes effective control over the region difficult, and it has done significant harm to alternative development activities in the region.

This is the wrong answer! Poor economic prospects? Low private-sector investment? Widespread will to switch to legal crops? Guerrilla presence and insecurity? These are all reasons to invest generously in Caquetá's development, not to shun the department completely. Especially at a time when Caquetá is playing partial host to the most ambitious military operation in Colombia's history, and while coca eradication is taking money - albeit illegal money - out of the local economy.

Does USAID really mean to say that it will only invest in zones where the economy is already viable and where guerrilla presence is low? Does the United States make similar choices in Iraq, too? ("Forget about the Sunni Triangle, let's get the electricity flowing in the few towns where the locals are happy to have us.") If so, that would explain quite a bit.

Why, when the U.S. military is supporting a huge military operation to recover territory in Caquetá, is the rest of the U.S. government refusing to help Colombia's civilian state cement gains by giving people clean water, farm-to-market roads, and a functioning judiciary? How could it possibly make sense for residents of a historical guerrilla stronghold to be subjected to a strategy of all stick and no carrot - combats, mass arrests, searches and fumigations but no other aid?

Unaccompanied as it is by economic aid, the U.S.-supported "Plan Patriota" offensive sweeping through Caquetá brings to mind a basic counterinsurgency text, written by French army Lt. Col. David Galula, that Ricks' book quotes at length. "[S]ystematic large-scale operations," it reads, "because of their very size, alleviate somewhat the intelligence and mobility deficiency of the counterinsurgent. Nevertheless, conventional operations by themselves have at best no more effect than a fly swatter. Some guerrillas are bound to be caught, but new recruits will replace them as fast as they are lost."

Supporters of the current policy in the U.S. and Colombian governments tell me that I worry too much. Bush administration officials are optimistic about how things are going in Colombia. (But then, they seem to see progress everywhere, don't they?) They repeatedly point to the gains of President Álvaro Uribe's tough security policies - nationwide reductions in murders, kidnappings, and guerrilla attacks - often claiming that they are a result of Plan Colombia and U.S. policy.

But the basics of counterinsurgency doctrine tell me that I should worry. The Colombian government's territorial gains seem to last only as long as the military remains present in large numbers, while the civilian state presence remains negligible and the local economy remains depressed. The FARC's entire Secretariat and General Staff, and nearly all front commanders, remain at large. The guerrillas remain very wealthy, thanks in part to the policy's failure to reduce drug-crop cultivation.

While Uribe's security strategy has reduced violence in cities and along main roads, conditions remain as dangerous as ever in the neglected rural areas - like most of Caquetá - where guerrillas dominate and drug crops thrive. In Caquetá during the past fifteen months, the guerrillas have massacred town council members in the department's third-largest town, stopped all road traffic for several weeks, and laid siege to San Vicente del Caguán, the second-largest town, forcing severe shortages.

Some Colombian analysts worry that the FARC is merely in a state of "tactical retreat" and can easily re-emerge, a phenomenon described by counterinsurgency expert Robert Tomes in the Army journal Parameters: "Many times insurgencies will take strategic pauses to adapt, regroup, and develop new mobilization strategies. Too often a new regime will interpret this as victory."

Meanwhile, the United States is not much help, as it pushes a militarized, counterproductive model that ignores the basics of how to win over populations in insurgent-dominated areas. We may be relearning these lessons slowly, as the Army updates its old counterinsurgency field manuals and Pentagon civilians repeatedly screen The Battle of Algiers. But Caquetá makes clear that, for the most part, U.S. officialdom still measures progress in the number of insurgents killed, not in the number of citizens made safe, healthy and employed.

Journalist George Packer, who has also written an excellent book on Iraq, reminds us that counterinsurgency, when done right, subordinates the military dimension to these other goals.

The classic doctrine, which was developed by the British in Malaya in the nineteen-forties and fifties, says that counterinsurgency warfare is twenty per cent military and eighty per cent political. The focus of operations is on the civilian population: isolating residents from insurgents, providing security, building a police force, and allowing political and economic development to take place so that the government commands the allegiance of its citizens.

Our aid to Colombia continues to be the opposite: 80 percent military and 20 percent not. In key counterinsurgent battlegrounds like Caquetá, the ratio is more like 100 to zero. Without a large shift toward development aid, "Plan Patriota" and similar U.S.-supported efforts will end up being nothing more than fly swatters.

Bravo, Adam, for this post, as well as for documenting the feed plant disaster in Putumayo in your previous post at the CIP website.

I see you finally got ahold of that USAID map. Good for you.

While I don't disagree with your basic conclusion here, I would like to enrich the picture, as always, by introducing some considerations:

1) You can see on the map that the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is included in USAID's 2006-2008 objective areas. This is, as you know, a zone of conflict as much as Caequeta is. A significant portion of Putumayo is also included, as well as all of Narino, nearly all of the Pacific coast, and significant portions of the Santanders, all of which are zones of major conflict. This right here militates against your conclusion that USAID is investing only in areas where "guerrilla presence is low." In fact, field workers associated with the USAID programs you refer to have had more than a half dozen encounters with the FARC and ELN in this first year alone. Thankfully, only one of the encounters has been violent so far (the FARC blew up a greenhouse and farm mahcinery at a project in Santander, no one killed).

2) USAID's response to Congressman Almario that Caqueta "lacks sufficient economic potential and there is very little private-sector investment" does have some sense to it when you consider that USAID's budgeted $300 million (it was more like $400 million back in April, they keep threatening to cut it back--rumors that it's being diverted to Iraq)in development assistance is scarcely enough to cover, in my estimate, some 25-30 rural productive projects per year, about 4.8 per USAID zone of focus (map)--and this with the majority of project funds leveraged from non-USAID sources (I think the average USAID participation in these rural projects is like 20%). So the money, even though it's quite a lot compared to most development projects, isn't all that much. Furthermore, USAID programs deal with entities, not individuals (and this is logical, given the scale of the funds and results desired). Many times these entities are conniving middlemen ("subcontratistas," "operadores," "ejecutadores," etc.) who basically embezzle the money, or well-established well-connected businesses who don't don't really it; but other times these entities are honest cooperative organizations comprised of the right people, the small scale producers themselves, growing or at risk of growing coca. If rural producers are not organized into cooperatives in Caqueta, it's understandable why it would be difficult for USAID to deal with them on the scale that it needs to (the scale of thousands of hectares). All of this is, in part, why the USAID programs are geared toward areas where there is at least a modicum of security, infrastructure, and producer and value chain organization (moreover, I think it is a stretch to assert, as you do implicitly, that any part of Colombia is "economically viable," unless we are talking about the narco-economy). As for your argument that the US strategy should be 80% brain and 20% muscle, I think you're right on target. But given that the ratio is actually like 99:1 muscle to brains, well, I can have some understanding for the USAID strategy.

I would go on, but I've already gone on quite a bit, so I'll leave off here. Once again, good post, stimulating.

FYI- I signed in to CIP but the website wouldn't let me make my post there. That's why I've made it here.

Posted by: Rainer Cale | September 01, 2006 at 12:47 AM

Just one comment for Rainer Cale, who wrote that "(moreover, I think it is a stretch to assert, as you do implicitly, that any part of Colombia is "economically viable," unless we are talking about the narco-economy)"

I think that that this statement, perhaps common in the U.S. and elsewhere, shows an undeniable degree of superficiality and relative ignorance about the Colombian economy, which is not totally dependant on drugs at all. There are, and always have been, plenty of viable parts of the Colombian economy that have little or nothing to do with the drug trade per se. You would do well, if possible, to study the subject at length before making such a generalization. Other than saying that, I'm making no other claims or comments here.

Posted by: jcg | September 01, 2006 at 09:44 AM

What you have documented is mostly obvious, and so when people disagree it shows that it's important to say it.

One minor point.

"Israel, the United States' closest ally in the Middle East, ..."

Israel is not the United States' ally.

The USA is israel's ally.

People keep confusing those two, as if it's a symmetric relationship.

Posted by: J Thomas | September 01, 2006 at 11:21 AM

In response to jcg, it's true that I have a long ways to go before I have a solid grasp on the Colombian economy, and my statement was, perhaps, too sweeping and strident, and smacked of the tiresome stereotypes that are always being exchanged over Colombia in the US.

But what was Colombia's GDP last year? And how does that GDP measure up against the multi-billion dollar drug trade? Also, we are talking about an economy with something like 30% unemployment according to official stats, and probably more like 50% according to reality.

So, just in case people get the impression by Adam's "economically viable" that there are broad swaths of Colombia that have healthy, crisis-free, stable economies, well, I want to call that into question, at the very least. I would say the so-called "economically viable" parts of Colombia are in dire need of development assistance, mostly in the form of integrating and streamlining the value chain to bring down prices. (It's so sad to go into Carulla all the time and see loads and loads of apples, oranges, tangelos, etc., from Chile, and just a few pathetic mandarinas from Cundinamarca).

Posted by: Rainer Cale | September 01, 2006 at 11:45 AM

I want to thank Adam and Rainer for bringing our attention to a recipient of US military and other aid of the first order.

I would add the following to the discussion. It is true that we are far from figuring out how best to contain and diminish the strike capabilities of insurgencies. That is the case from both a military and a more global point of view. But the unspoken assumption of some proposals (here I'm thinking of Adam's point of view, with which I am nevertheless sympathetic) is that we know just what we are doing when we distribute economic aid. It is more often the case that the economic aid we distribute is non productive or even counter productive.

It would be nice to find a successful example of military and extra-military counterinsurgency efforts and learn why they worked. Who would like to cite relevant cases?

Posted by: John FH | September 01, 2006 at 01:43 PM

John FH- Mozambique may be worth looking at, both after independence in 1975 and during and after the 1984-1992 insurgency. There were periods of significant economic growth after both conflicts, including substantial foreign aid from the IMF, World Bank, FAO, and other agencies (USAID not among them). A rare case where the foreign aid seems to have been rather effective.

Disclaimer: I'm not saying that Mozambique's conflict was similar to Colombia's.

Posted by: Rainer Cale | September 01, 2006 at 07:38 PM

The best way to counteract the violence of an insurgency is not to create insurgencies through irresponsible and invasionary policies.

The example of Colombia is telling and deserves to be more widely discussed.

The United States of America has never been interested in the promotion of democracy except where its own strategic economic and political interests were best served, just as European monarchs were never interested in promoting Christianity except where their own strategic and political interests were best served.

I hope that we aren't making nit-picky cross-theatre comparisons at the expense of a larger argument for the validity of the idea of democracy promotion in the first place. Many parts of the Middle East are in dire need of political and social reform, but not at the direction of a government such as that of the US or the UK, which working together have overthrown more democratically elected governments than dictatorships, particularly in the western hemisphere.

The people of the US mean well in wishing for progress and reform abroad. Our government only means business, and often rather sinister business at that.

Posted by: Curt | September 04, 2006 at 10:23 AM

It is clear that the US government does not have it's priorities clear. "neglecting poverty and civilian governance" is a common error. If we had kept our promises outlined in the Millenium Goals (agreed to by almost every nation on earth in 2000), we would have made huge leaps toward eliminating the extreme poverty that makes insurgency a problem to begin with. We need to make sure our representatives make a stand for the Millenium Development Goals, or else we will never see the end of this intense world-wide conflict.

Posted by: stephanie | September 05, 2006 at 01:39 PM

runescape money runescape gold runescape money runescape gold wow power leveling wow powerleveling Warcraft Power Leveling Warcraft PowerLeveling buy runescape gold buy runescape money runescape items runescape gold runescape money runescape accounts runescape gp dofus kamas buy dofus kamas Guild Wars Gold buy Guild Wars Gold runescape accounts buy runescape accounts runescape lotro gold buy lotro gold lotro gold buy lotro gold lotro gold buy lotro gold lotro gold buy lotro goldrunescape money runescape power leveling runescape money runescape gold dofus kamas cheap runescape money cheap runescape gold Hellgate Palladium Hellgate London Palladium Hellgate money Tabula Rasa gold tabula rasa money Tabula Rasa Credit

Tabula Rasa Credits Hellgate gold Hellgate London gold

Posted by: runescape money | November 25, 2007 at 12:44 AM

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape gold

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

runescape money

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

www.runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

runescape.com

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

buy runescape gold

buy runescape gold

buy runescape gold

buy runescape gold

buy runescape gold

buy runescape gold

buy runescape gold

cheap runescape money

cheap runescape money

cheap runescape money

cheap runescape money

cheap runescape money

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape gold

cheap runescape money

cheap runescape money

rs2 gold

rs2 gold

rs2 gold

rs2 gold

rs2 gold

rs2 gold

rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

cheap rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

buy rs2 gold

Posted by: cheapgold | November 30, 2007 at 02:23 AM